He oneone ahau

nā Bronte Perry - Jan ‘23

From the moment the missionaries landed in the Bay of Islands, the assimilation of the whenua became integral to wider assimilation of my tūpuna. The infamous missionary Samuel Marsden believed “commerce promotes industry - industry civilisation and civilisation opens up the way for the gospel”(1). So the first mission houses were run as farms, taking advantage of the knowledge my tūpuna had as gardeners in order to evangelise civilisation through labour. Slowly the missionaries obfuscated one mātauranga for another. For many of my tūpuna, Io became Jehovah, Christian morality overtook tikanga and our way of being shifted to prop up empire.

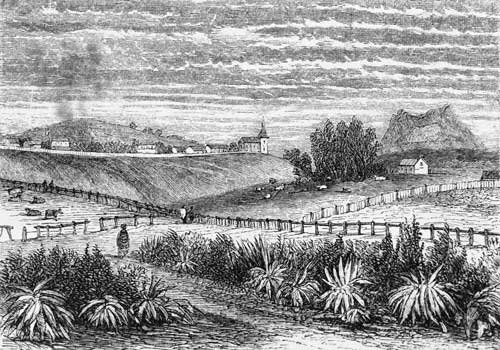

The Waimate Mission Station in 1845 (2). A large farm with sheep, cattle, horses, gardens and orchards. It was the first inland mission farm house and the CMS first successful farm. It allowed British missionaries to be less dependent on Māori for food/survival and begin evangelising inland hapū. Charles Darwin stayed briefly at the house and commented at the sight beyond the farm fence: “The whole scene, in spite of its green colour, had a rather desolate aspect. The sight of so much fern impresses the mind with an idea of sterility…”(3) only to later realise the fern itself is a sign of prosperous soils. Foreshadowing settlers’ mentality towards the taiao of Te Tai Tokerau.

What followed for Te Tai Tokerau was two centuries of settler industries that drove boom and bust economies at the cost of the health and prosperity of Papatūānuku. Gum digging uprooted swathes of kānuka scrublands that had once grown out of ancient kauri forests, only to be left lifeless empty bogs. Lush native bush was cleared to make way for the timber industry and wetlands were drained to create pastures. And on it went, the manipulation of our whenua to fill settlers insatiable hunger for land, capital and the empire's promises of milk and honey. As the whenua grew sick, so did we. In our disconnection much of our mātauranga was lost, our taiao discreated and polluted, our whenua stolen, even the very bones of our tūpuna were uprooted and sold. Hone Sadler lays out the hakapapa of loss as: ‘Landlessness cohabits with The Saddened Heart and begat Sudden Death’. (4)

The sacred house of Ngāpuhi is made upon the warmth of Papatūānuku as its floor, the great overarching embrace of Ranginui as its roof and our Maunga as its pillars. As descendants of atua, we are born of this whenua from which our mana derives - we are built from the richness of dirt. To be overcome by what was taken from us, discredits those past and present who have safeguarded the mātauranga we still hold. Although our taonga were ripped from the earth, I reflect on how much we have sown into her and her into us. We understand ourselves to be part of a vast ecostructure; as Emily Rākete describes: “We are not beings who are of the land but the land itself in the act of being. We are a function of the ecology, we are ecology foremost.”(5)

We understand whenua is never just a material component, but an active participant, as Papatūānuku is atua, tupuna and whenua simultaneously. Sadler speaks of the role of hakapapa and whenua in the evolution of Ngāpuhi mātauranga. He writes that for many of our whanaunga across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa their traditions speak to the marriage between Papatūānuku and Tangaroa, reflecting their relationship to their motu. So when our tūpuna arrived to Aotearoa they recognised that unlike Hawaiki, Papatūānuku and Ranginui were the primary entities, thus for many iwi Papatūānuku is in union with Ranginui.

We can observe the genius of our tūpuna as navigators, scientists and explorers in moving through the world in search of our place within and as the ecosystem. As Sadler denotes: “Kaupapa/Kawa is enduring because it is built on a firm foundation and that foundation is Papatūānuku… there is the beginning of our kith and kindred relationships from our deities we have been inextricably bound. When our ancestors came here they all emerged from the same womb.”(6). So just as the tohunga whakairo emulates the movements of the maggot carving flesh from bone in the creation of waka tūpāpaku, we observe our interconnectivity within and as ecology to ground our tikanga as there is no severance between tangata and whenua.

This remarkable Kauri recorded the climate and makeup of the atmosphere through its annual rings forming a climate archive - a whakapapa. From this genealogy scientists can learn the ages of other plant, human and animal artefacts, from as far back as tens of thousands of years. Satelite data suggests that the Earth’s magnetic field is changing rapidly and through analyses of this whakapapa, we can better understand the possible effects of a geomagnetic event in the near future. All things have a whakapapa, connecting us all like mycelium. (7)

Generations of urbanised Ngāpuhi are reconnecting to their rohe, bringing with them a unique set of skills and knowledge. And along with those who remained to keep the ahi kā burning, we continue to drive our revitalisation. Papatūānuku herself continues to guide us as Ngāpuhi, revealing to us old taonga buried by our tūpuna or new rawa taiao to continue our revitalisation. Within my rohe an ancient kauri was unearthed in the sediments of Ngāwhā in 2019. With its arrival brought new knowledge too. This kauri experienced what's called the Laschamps geomagnetic excursion - an unbalancing of the earth's magnetic field 42,000 years ago. An event that could be only confirmed by the uniqueness of our whenua and the flora that grows from her. These soils not only produced and sustained a single kauri for 1600 years but also preserved it so perfectly for a further 42 millenia that some of the leaves and cones were still green. And now this taonga will be shared amongst the hapū of Ngāwhā, adding to the continued rediscovery and development of our practices thanks to what the whenua has shared with us

So I think of those practitioners and tohunga who returned to the whenua in search of the many aho of knowledge that lay waiting to be rediscovered: Hekenukumai-ngā-iwi Puhipi, Pou Awhina, Symphony Morunga, Sonia Snowden, and Manos Nathan to name but a few. As long as we have dirt - whenua - Papatūānuku, we always have a way of revealing lost knowledge. Regrowing of our interconnections through curiosity, whanaungatanga, hakapapa and whenua. Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua (8), weaving back through the aho into a new basket of knowledge.

Despite the wailings of settlers to the contrary, Te Tai Tokerau is still bursting with taiao. From the plentiful bounties of kokowai, to the soils that support Tane Mahuta in the great Waipoua forest - our whenua is very much fertile. As deep and complex is the beauty of our whenua, so too are our ways of being, to be Māori, to be Ngāpuhi. Within the whenua we continue to sow. So no matter how far we stray, we will always be guided back to the mātauranga embedded within her.

Whatungarongaro te tangata, toitū te whenua -

As man disappears from sight, the land remains.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Ballantyne, Tony. Entanglements of empire: Missionaries, Māori, and the question of the body. Auckland University Press, 2015.

2. Bridge, Cyprian, 1807-1885 :Waimate Mission Station in 1845. [Engraved by] J. Whymper, from a sketch by Col. Bridge. [London, 1859]

3. Darwin, Charles. Charles Darwin's Beagle Diary. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

4. Sadler, Hone. Ko Tautoro, Te Pito O Toku Ao: A Ngapuhi Narrative. Auckland University Press, 2014.

5. Rākete, Emilie. "In Human: Parasites, Posthumanism, and Papatūānuku." The Documenta 14 Reader (2017).

6. Sadler, Hone. Ko Tautoro, Te Pito O Toku Ao: A Ngapuhi Narrative. Auckland University Press, 2014.

7. https://www.earthtouchnews.com/natural-world/natural-world/swamp-sentinels-what-we-can-learn-from-new-zealands-ancient-kauri-trees/

8. “I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past” - Whakataukī

Bronte Perry

Bronte Perry is a South Auckland born and bred artist based in Tāmaki Makaurau. They graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts with Honours from Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland. Throughout their multidisciplinary practice Perry embodies whakapapa, whanaungatanga and lived experiences to explore socio-political contexts.